Social recognition (in the form of positional, moral or emotional recognition) appears from the disintegration approach perspective to be the consequence of social integration that is succeeding. Three central active principles of denial of recognition were listed: the avoidance of inferiority and damage to self-esteem, restoration of norms and the lack of alternatives as a learning process. The specific pattern of action individual players choose in specific situations depends on the functionality of the pattern of coping in compensating for the damage to recognition, on individual and social opportunity structures and on biographical dispositions. Social competencies, attributions of responsibility and social comparison processes play an important role in this and are in part a direct constitutive element in the operationalization of states of integration.

1. The Disintegration Perspective

The Bielefeld disintegration approach seeks to explain the diverse phenomena of violence, right-wing extremism, ethno-cultural conflicts, devaluation and repulsion of weak groups. From a conflict theory perspective each can be viewed as a specific, problematic pattern of dealing with states of individual and/or social disintegration. Disintegration marks the failure of social institutions and communities to deliver existential basics, social recognition and personal integrity. The disintegration approach accordingly explains the aforementioned phenomena as resulting from a society’s unsatisfactory integration performance.

This article aims to examine more closely and explicate the two following theses in particular:

a. A basic assumption of the disintegration approach is that the scale and intensity of the said patterns of behavior increases in line with the extent of experiences and fears of disintegration while the ability to control them decreases. No direct, determinist connection at an individual level is assumed, but instead it is assumed that individual breaking-point factors, milieu-specific mobilizations and opportunity structures determine the choice of specific pattern of coping (apathy and resignation also being conceivable “solutions”).

b. It is also maintained that not only all of the above-mentioned patterns of coping have been preceded by specific disintegration experiences and injuries to recognition but that focusing on this common background pattern serves to integrate theories. An attempt is made to suggest a general theoretical model of explanation since in our opinion explanatory viewpoints based on individual theories do not go far enough.1

2. In Search of an Integrative Theory of Violence

Let us begin examining the question we have formulated with the second, more far-reaching thesis. Why raise the issue of an integrative theory at all?

First, in the context of the phenomena under consideration one comes across repeated calls for a closer synthesis and integration of existing theoretical perspectives. The background to these calls is the confusing array of explanatory approaches of widely differing provenances. Among others, deprivation, anomie, control, interaction, socialization and learning theory perspectives, to name but a few of the most important, compete with each other in the set of explanations for the phenomena under consideration.

Second, it should be amply clear by now that no theory can lay claim to an explanatory monopoly because a number of different causal processes and mechanisms are recognizable. Hence taken individually control theory, learning theory or stress theory interpretations are rightly regarded as undercomplex (cf. inter alia Baumeister/Bushman 2003: 479; Albrecht 2003: 624).

On the Undercomplexity of Current Theories of Violence

Undercomplexity results not only from the disciplinary nature of violence theories, although an initial handicap can be seen here. The disciplinary view is often reproduced in overviews of aggression or violence theories if location within a discipline (sociological, socio-psychological or psychological) is chosen as the common pattern of classification (cf. inter alia Schubarth 2000). Other classification models try to avoid the disciplinary link by choosing thematic focuses (e.g. social structure, socialization, individual, cf. Möller 2001) in which priority is given to the respective levels of examination (macro, meso or micro perspective). In fact this only amounts to a partial regrouping of theoretical approaches without overcoming the basic disciplinary background. Other classification patterns seek to identify central active principles that can be used to summarize explanatory approaches that employ similar arguments into clusters, for instance subdividing them into deprivation theorems, reflection theorems and social character theorems (cf. Kliche 1994 quoted according to Peters 1995: 27). This appears to be both the most conceptually demanding and promising and the least used path to knowledge.

The undercomplexity of current theories of violence is manifested in various ways. First, we are dealing with rather general theories that were not specially developed to explain violence as a pattern of action but are generally geared to explaining social actions (and indeed both prosocial and deviant or conspicuous actions). This reproduces the straitening of the respective “theory of origin” in which the main focus is on one dominant explanatory principle, usually regardless of differentiations by culture, gender or age-specific requirements or peculiarities. Sociological decision theories or rational choice theories, for example, argue that action takes place on the basis of cost-benefit calculations alone. In socio-psychological theories, in the case of behaviorist concepts action is seen as a reaction to external stimuli (for example frustration-aggression), while cognitive learning theories see it as the outcome of knowledge and individual psychology theories such as psychoanalytical theory say that the need for closeness and attachment determines action.

The situation is somewhat different with theories conceived specially to explain the genesis of (crimes of) violence. Some theories have difficulty in finding empirical confirmation because the effect of possible causal factors was over-interpreted and interactions with other influencing factors were overlooked. This applies for instance to anomie theory, which focuses mainly on the lack of legitimate ways and means to achieve individual goals that are highly rated by society and, invoking the “innovation” pattern of reaction, sees the choice of illegitimate means as the cause of individual (crimes of) violence. The fact that, contrary to theoretical expectations, several studies failed to find any negative correlations between membership of a social stratum and delinquency is obviously due to reverse chains of effect since, in the case of juvenile delinquency, the parents’ status has both indirect negative and indirect positive causal effects that seem to cancel each other out overall (Albrecht 2003: 616). The delinquency-reducing effect in underprivileged strata of socialization geared more strongly toward family cohesion and less strongly toward self-assertion and success was not adequately anchored in the concept.

Other theories seem appropriate only to explain the reproduction of a violent pattern of behavior, but not its genesis. They include, for instance, the theory of differential association, the basic idea of which is that criminal behavior is behavior learned as the result of differential contacts that rate violence positively or that arise in the family due to membership of a certain cultural milieu or experiences in early childhood. Thus this theory says nothing about how dispositions of this kind originated. Who rates violence positively and why (cf. also 2003: 613)? The same applies to part of the learning theory explanation of deviant behavior. The learning of violence in the form of model learning or cognitive learning mainly explains the reproduction of behavior, but not its origin (cf. Nolting 1999: 109)2.

In addition to the above-mentioned points of criticism, there are a number of others relating to single theoretical constructs which for reasons of space we will refrain from exploring further here. However, if one looks for a system in the criticism, two points strike one:

Interruption of Theoretical Chains of Effect by Individual Breaking-point Factors

The pattern is repeated whereby the inclusion of a single moderating variable is capable of negating the arguments of an approach in their entirety. This affects, for instance, as widely varied theoretical concepts as social inequality, frustration-aggression or learning from experience in the form of experience of punishment.

As regards the significance of opportunity structures and social inequality, Albrecht in particular has pointed out that relationships between membership of a social stratum and being found guilty of (violent) crime which used to seem theoretically convincing can now only be confirmed to a limited degree because ultimately “the type of causal attribution of success or failure” in situations where the achievement of goals is blocked is probably the crucial factor leading to the choice of a particular pattern of reaction (Albrecht 2001: 28). Here, attributions of responsibility or patterns of accountability (who or what is responsible for my specific situation?) as relevant quantities for defining social situations of personal failure negate formerly persuasive macro-sociological patterns of argumentation.

As regards the classic frustration-aggression theory, which for some time has been discussed in the extended forms of frustration-aggression-arousal thesis or frustration-impulse thesis (cf. Bierhoff/Wagner 1998; Nolting 1999: 87f), specific social competencies especially have a relativizing effect. Individuals who have good social competencies not only have better adjustment strategies but also an active system for managing their environment, so they find it easier to bear, avert or transform the frustrations suffered (cf. Schmidtchen 1997: 218f). That explains why individual dispositions to anger result in different outcomes and are capable of halting the chain of effects that is deemed so significant especially in forms of emotional aggression (cf. Nolting 1999: 148f).

A third example relates to learning from experience in the form of experience of punishment. It is generally accepted that punishment, especially of a type that includes aggressive elements, can encourage aggression because it acts as a model or leads to imitation. However, empirical research has shown that even a high level of punishment only results in a disposition toward violence if the punishment is not simultaneously balanced by attention (cf. Albrecht 2003: 624). Thus warmth and emotional attention cancel out the chain of effects based on learning theory.

As the quintessence of these analyses the obvious thing would be to shift the focus to a socialization theory perspective. How are individual attribution patterns, social competencies and emotional security cultivated? That would place the emphasis on control theory. The classic control theory perspective of research into violence draws on the fact that by means of attachments, commitment and specific normative beliefs acquired during the socialization process people develop norms of their own that prevent them from being susceptible to deviant behavior. However, this theoretical position is rightly criticized for dismissing over-hastily the role of social structure strains (cf. Albrecht 2003: 629). This again raises the fundamental question whether strains or direct socialization influences lead to deviant behavior. In the former case, for instance, in principle everyone would be susceptible in a situation in which they were overtaxed, whereas in the latter only those persons lacking in specific (personality) characteristics (impulse control, tolerance of frustration, etc.) would be susceptible. Now, all attempts developed to solve this question are based on a firm assumption that these two causal complexes are interconnected or mutually dependent (cf. inter alia Hurrelmann 1990: 104f; Helsper 1995: 138f).

From the control theory perspective this formula can also be applied to the case considered above concerning the genesis or prevention of violence. For example, in the context of socialization in the family for a child to adopt its parents’ prosocial standards and value concepts it must feel acknowledged by the interaction between parents and child (cf. Hodges/Card/Isaacs 2003: 497). Parents’ ability to offer their children recognition by setting an example of autonomy, mutual respect and consideration is likely to depend substantially on the nature of their own social, economic and socio-cultural circumstances, as it were their own sources of recognition (cf. Helsper 1995: 138), that is on the extent to which they themselves act on the basis of assured recognition. Once again, the indications mount that problems of recognition seem to be of crucial importance to the question of communicating, encouraging and passing on the aforesaid competencies and patterns of accountability.

Damage to Recognition as a Central Element of Theory

In the search of linking elements among the argumentation based on specific theories it is striking that questions of damage of recognition always refer to one central aspect.

In numerous cases, the question of recognition tends to be broached implicitly. We have already explained that the control theory pattern of the internalization of standards3 can only hold good if the related interaction of respect and mutually based recognition is maintained. In subculture theory interpretations the central motive for joining subcultural youth groups and gangs is found to be the search for recognition and belonging (Heitmeyer 1992). Since joining gangs is also said to be linked to a state of collective frustration among youths from lower social strata who are unable to achieve middle class-oriented goals (due to school and occupational selection processes), subculture theory and deprivation theory interpretations must in any case not be treated as fully and clearly separate. Problems of recognition are central to this argumentation, too. If one sees no opportunities to compete successfully with others for the same goal one wants to be different, one supports different, subcultural norms such as gaining prestige by means of physical strength, honor, etc4

Life course theory, which mainly examines the question in which cases violence should be regarded as a stable behavior pattern and when as a youth-specific, as it were passing behavior pattern, says in summary that the stability of aggression/crimes of violence in a person’s life is based more strongly on the stability or instability of the type and quality of their social relations and close personal attachments than on any individual predisposition (Albrecht 2003: 635). Hence it sees an empirically-based opportunity to amend dispositions acquired in early childhood, which can arise because children are unsure of others’ attachment, expect excessive social recognition or have an over-sensitive perception of threat (Petermann 1998: 1017), by means a child-oriented upbringing that encourages prosocial behavior5.

In the theories mentioned thus far, although the question of recognition names central aspects without which the respective anticipated chains of effect would not be realized, or not in the manner described, it tend to be broached implicitly. It is a different matter with the following theoretical complexes: deviant behavior to defend self-esteem, aggression as a result of a threatened self and the theory of social interactionism. Here, the issue of recognition forms the hub around which the entire argument revolves. The first concept, which is in the tradition of social psychology, is based on the idea that every human being has a fundamental need to maintain and/or enhance self-esteem and that when it is diminished deviant acts are an appropriate, logical option for finding new recognition (cf. Albrecht 2003: 627). In the concept of aggression as a result of a threatened self, aggression is interpreted as a helpless attempt to bring feelings of fear and threat – as a reaction to frustrations and hurt – under control. Aggression and violence in this sense is a psychological emergency signal that children and juveniles especially use to attract more attention, more attachment and acknowledgement (cf. Schubarth 2000: 22f). Meanwhile, the theory of social interactionism emphasizes three complexes of motives as causes for violence-prone behavior: social control, justice and identity motives. Fundamental recognition deficits can be identified in all three types of motivation. As regards social control motives, a lack of cooperative resources (absence of social skills, lack of education, status or prestige, etc.) is blamed for violent acts or the subjective existence of a belief that the individual’s goals can only be achieved through violence. An absence of alternatives is the dominant pattern. In the case of justice motives and identity motives violent action is a direct reaction to damage to recognition and is aimed at restoring justice, gaining the desired respect or saving face (cf. Tedeschi 2003: 465ff).

There remains a small group of theoretical approaches that discuss recognition elements neither implicitly nor explicitly. This raises the question what relationship these theories can have to a focus on recognition. They include, for instance, rational choice-based utilitarian theory or the theory of the deterrent value of punishment, which sees criminal action as a function of a cost-benefit calculation on the part of the perpetrators. This seems to be significant from a recognition theory perspective to the extent that persons who have a given affinity with violence because they have suffered injury to recognition or are seeking to restore recognition may include a cost-benefit calculation in their deliberations whether to commit acts of instrumental violence (less so, or not at all, in the case of emotional violence). Thus the deterrence theory perspective could be used to explain as it were a peripheral condition (probability of success versus probability of sanction), no more and no less.

Without wishing to claim that this list is complete, in our opinion most theoretical concepts see the central significance of objective injuries to recognition (or subjective fears of them) for explaining affinity with violence. However, if this complex of significance plays such a central role, the question arises of reinterpreting from this integrating perspective the theoretical backdrops that have largely been considered in isolation until now. If one places the recognition motive at the centre, the apparent randomness of the motives for violence discussed until now acquires a new order. In a remarkable listing, Peters some time ago described violence as “an expression of the lack of other control resources, as a means of repairing damaged identities, as a consequence of authoritarian styles of upbringing and family structures, as a means of producing group integration, as a reflection of the ‘me first’ society, as a reaction to violence” (1995: 27). Now, from the recognition theory perspective a uniform background pattern can be identified to things that in individual theory perspectives existed relatively unconnected alongside each other. Apart from “a reflection of the ‘me first’ society,” all the motives listed above were traced back as relevant to recognition. The “reflection of the ‘me first’ society” motive is likewise directly related to recognition, since the argument here is that in their actions young people are only radicalizing the social postulates of self-assertion and differentiation that they have grown familiar with in the form of instrumental work and social relations in which human beings are treated as objects rather than subjects (cf. inter alia Heitmeyer 1994: 47, 57ff).

Pursuing the proposed thesis further leads to the question what precisely one should understand by recognition and what relation it has to social integration.

3. Recognition and Social Integration

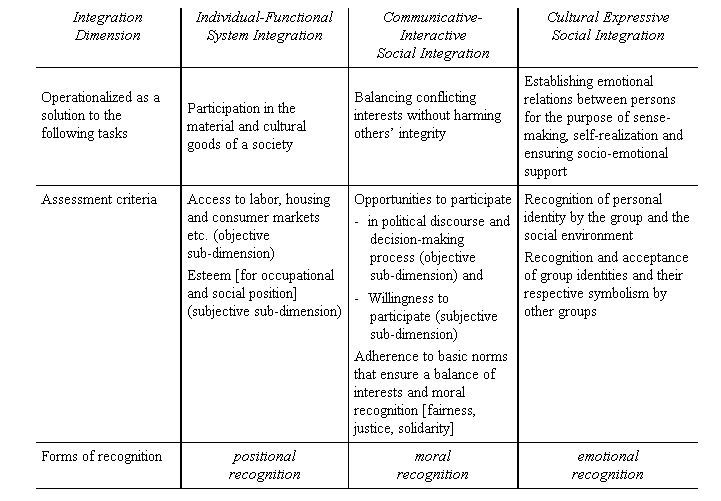

From the disintegration approach perspective recognition comes about as a consequence of solving the problem of social integration. Following and further developing Bernhard Peters’ initial thoughts on the matter, the disintegration approach takes the social or societal integration of individuals and groups to mean a successful relationship between freedom and attachment in which three specific problems in particular are solved satisfactorily (cf. Fig. 1):

First, at the social-structural level there is the problem of participation in the material and cultural goods of a society. As a rule, this is objectively ensured by sufficient access to labor, housing and consumer markets, but subjectively it requires a counterpart in the form of satisfaction with one’s occupational and social position.

Second, at the institutional level (socialization aspect) a balance has to be struck between conflicting interests without wounding people’s integrity. From the disintegration approach perspective this calls for adherence to basic democratic principles that guarantee the (political) opponent’s equal moral status and that those involved can rate as fair and just. However, the negotiation and specific formulation of these principles in individual cases also presupposes corresponding opportunities and the willingness of those involved to participate.

Finally, at the personal level (communalization aspect) it is a matter of establishing emotional and expressive relations between people for the purpose of making sense and self-realization. This calls for considerable attention and attentiveness resources, but also for allowing space to be oneself and balancing of emotional support with normative demands so as to avoid crises of meaning, disorientation, diminution of the sense of self-esteem or diffusion of values and identity crises.

Figure 1: Integration Dimensions, Integration Goals and Criteria for Assessing Successful Social Integration

Source: Anhut/Heitmeyer 2000: 48.

In the disintegration approach, these three tasks are said to be achieved by individual-functional system integration (structural level), communicative-interactive social integration (institutional level) and cultural-expressive social integration (socio-emotional level). Clearly, the disintegration approach discusses the establishing of social integration on a voluntary basis. In modern societies, this characteristically takes place or may take place by balancing interests, recognition and consensus building rather than by earlier forms of integration in traditional societies, where a subjective sense of belonging frequently tended to be based on non-voluntary mechanisms such as duress and pressure to conform. The disintegration approach perspective sees the successful accomplishment of these tasks as resulting in the provision of positional, moral and emotional recognition and self-definition as belonging to the relevant social group. On the basis of social integration, voluntary acceptance of norms can also be expected. In contrast, in states of disintegration the effects of one’s own action on others no longer have to be specially taken into account. This encourages the development of antisocial attitudes and creates a risk that violence thresholds will be lowered.

Background Processes of Disintegration

Which social processes does the disintegration approach consider to be responsible for an increase or decrease in social integration and/or a loss of recognition?

At the social-structural level, social polarizations reduce access opportunities and achievable gratifications in the realm of individual-functional system integration. Meanwhile, an additional process of individualization propagates the concept of man as an autonomous, competent, successful individual, thereby intensifying the pressure on individuals to present themselves as successful. Yet despite the increased pressure for placement the opportunities and risks of social positioning are still spread unevenly. This leads ever more frequently to disappointments for the losers in the modernization process and unleashes feelings of resignation, impotence and rage.

Seen institutionally, ideas of rivalry and competition at school and at work, instrumental work and social relationships and a consumer-oriented lifestyle that is intent on money, status and prestige encourage self-interested tendencies like having to get one’s own way, social distinction and exclusion. This situation is aggravated by the change in political climate that has been evident since the 1980s (cf. Hengsbach 1997) and appears to favor the teaching of egocentric, competition-oriented attitudes and to promote patterns of behavior that destroy solidarity.

At the socio-emotional level ambivalent individualization processes encourage among other things a growing instability in relationships between couples, as a result of which family disintegration can have a harmful effect on the conditions in which children are socialized. The emotional overtaxing of those responsible for their upbringing is due especially to the fact that individuals increasingly demand relationships based on equal rights while simultaneously experiencing many forms of inequality. This emotional stress is often released in frustration, insecurity and a generally higher potential for tension and conflict. In turn, the instability of family relationships detracts from children’s self-experience and the recognition that is required to build a positive self-image (cf. Peuckert 1997). Consequently, auto-aggressive tendencies to harm others and conspicuous behavior in children would be directly connected to the extent of family disintegration.

Assumptions Concerning the Effect of Disintegration

However, the increase or decrease in the degree of social integration and the accompanying changes in recognition options only provisionally express the extent to which the potential for dysfunctional ways of coping with disintegration is expanded or reduced. The forms of coping chosen by individuals are decided in particular by the coincidence

. of biographical experiences (competencies, patterns of accountability etc.) with

. specific opportunity structures such as integration into social milieus (group pressure/compulsion to conform) and the

. function of the chosen pattern of behavior in compensating for damage to recognition.

In order to answer the question as to the functionality of the chosen pattern of behavior in compensating for damage to recognition, we must be clear how injuries to recognition work in fact. Starting by differentiating between dimensions, three basic active principles can be identified:

a) Avoidance of inferiority and damage to self-esteem,

b) Restoration of norms

c) Lack of alternatives as a learning process.

On a): What does denial of positional recognition mean and what effect does it have?

Human beings perceive the denial of positional recognition as a personal failure that undermines their self-confidence. That is why people tend to endeavor to avoid this kind of damage. Several possibilities for coping with this situation exist. As is known inter alia from unemployment research studies since the early 1930s, until now apathy and resignation have remained the dominant patterns of reaction to experiences of this kind (cf. Eisenberg 2002: 13). Another option for maintaining a positive self-image in the face of ongoing strains is to blame others for one’s own fate (the “scapegoat phenomenon”) and to invoke prejudices and concepts of enemies in order to compensate 6 Finally, violence suggests itself in principle as a possible outlet to compensate for feelings of weakness and/or to maintain one’s sense of self-esteem. There is thus a wide range of possible “functional solutions” to this form of damage to recognition.

On b): What does denial of moral recognition mean and what effect does it have?

There seem to be two dominant forms; first the feeling that one’s own existence is experienced as not being of equal value and not having equal rights, e.g. due to non-membership of social groups or non-acceptance in the case of formal membership of groups or society; second, the impression that basic principles of justice are being violated although, for instance, the individual feels that he or she or his or her own group makes a relevant contribution to the collective social or societal good yet still experiences treatment as an inferior. In addition to cases where the individual feels himself or herself to have been treated disadvantageously or unjustly, one must include cases where the person himself or herself is not disadvantaged but formulates the feeling of injustice on behalf of others. Here, violence may be employed as an option for restoring justice (restoration of norms, cf. for example the “restore justice” principle in Tedeschi/Felson 1994) or to regain respect (assertion of identity). Unlike the “avoid inferiority/damage to self-esteem” pattern of motives, however, this is not necessarily done at the cost of persons or groups susceptible to discrimination but now tends to be aimed at persons or groups who appear to be privileged7. The expressive violence of young migrants in the suburbs of French cities who by their actions aim to symbolize “look, we exist, we are no rats” is an example of the latter complex.

On c): What does denial of emotional recognition mean and what effect does it have?

Denial of emotional recognition means to experience no or too little esteem or attention in important intimate social relationships, to receive no emotional support in situations of emotional strain, to have no contact person to discuss problems with, to have no autonomy, etc. As regards the question how affinity for violence originates, particularly in children and juveniles (and how it is subsequently reproduced in adulthood), two different paths appear to be significant. First, direct learning of violence can be observed inter alia in the form of a repeatedly reinforced cycle of violence in which experiences of violence in childhood and the subsequent use of violence against family members in adulthood are repeated (cf. Schneider 1990: 106). The characteristic features of this form of learning of violence, in which violent relationship patterns are sometimes handed down through generations, are authoritarian, hostilely deviant upbringing behavior on the part of parents (in which physical punishment functions as a model) accompanied by a lack of emotional warmth, which makes children feel humiliated. Along with this form of direct “learning by model,” there is a second form in which violence is employed as a pattern of dealing with conflict because other means of coping are not available due to the lack of specific social competencies and the existence of development deficits such as lack of empathy, identity disorders and disorders of self-esteem. Often the specific background to this pattern is insecure or disorganized attachment experiences which result in the development of problems in recognizing one’s own feelings and the feelings of others and in reacting empathetically to them. Children do not learn a constructive model for integrating negative feelings and for being able to deal with them in a constructive way. Development deficits in the emphatic shaping of relationships, systematic overtaxing, low tolerance of frustration, a low sense of self-esteem and vulnerability are the consequence. These children are relatively helpless in the face of difficult family and school relationships and use violence to defend themselves, to compensate for weakness or to retain a minimum of self-esteem (cf. inter alia Cierpka 1997: 159f; Ratzke/Cierpka 1999). In this respect one can speak of “the lack of alternative as a learning process.” However, to consider this only from the aspect of learning theory would be not to go far enough. Even if learning is based directly on experience and models, the reproduction of behavior is not necessarily attributable solely to the learning process as such. It has been estimated that around a quarter of all persons who were ill-treated and/or rejected as children go on to develop a social behavior disorder, which means that for the majority of ill-treated children this background of experience is insufficient as a compelling explanation of later violence. At the same time, it was established that those who break out of the cycle of violence (the non-repeaters) had in childhood at least one person in whom they could confide their worries and/or went on to live in a fulfilling partnership (Ratzke/Cierpka 1999: 30). Here, too, it is evidently the existence of emotional recognition that decides on the version or reproduction of the pattern of behavior, which is why the basic learning theory backdrop is in urgent need of expansion to include a recognition theory perspective.

It is thus possible to identify three basic principles of the effect of violation of recognition – the quest to avoid injuries to self-esteem, the need to restore norms and assert identity and the lack of an alternative pattern for dealing with conflict. However, as yet no preliminary decision has been taken as to which specific pattern of reaction will emerge in an individual case. As we have seen, violence can pattern of coping with problems with which affinity is felt, regardless of the specific sources from which the damage to recognition is fed. At most one would expect the gravity of the injury to recognition and whether it emanated from specific other persons (on whom one possibly wants to or must take revenge) or from “society” in general to affect the choice of the specific pattern of coping.

However, this raises the fundamental question as to the nature of specific configurations of effects, for example whether specific injuries to recognition in certain integration dimensions predispose to specific patterns of reaction or not. In principle, three different configurations of effects are conceivable.

First, it would be imaginable that damage to recognition that is fed primarily from one integration dimension also causes one specific pattern of reaction, for instance that while real rivalry reactions and subjective feelings of disadvantage might be primarily responsible for xenophobia, national-authoritarian or right-wing extremist attitudes are chosen because they are the best means of combating disorientation and feelings of impotence and individual readiness to resort to violence essentially springs from the world of experience of severe corporal punishment, psychological humiliation and a hostile social environment. This would mean that the choice of particular pattern of coping depends primarily on which pattern of coping promises to most effectively limit or compensate for the recognition deficit that has arisen.

Second, it would likewise be imaginable that in principle every pattern of coping could be a reaction to different prior injuries to recognition. In that case a possible nucleus of damage to recognition would emerge only in the choice of specific variations of a pattern of reaction. Albrecht (2003: 639), for instance, considers –with regard to our desintegration approach – it conceivable that recognition deficits in the social-structural dimension are primarily responsible for the risk of status-securing violence (e.g. procuring of status symbols), that disregard experienced in the institutional dimension is a key factor in politically motivated and collectively occurring violence (e.g. xenophobic violence) and that all kinds of emotional deprivations give rise to identity- and esteem-securing violence (tests of courage, etc.). Plausible as this proposal sounds from in terms of a macro-perspective explanation or reconstruction of the causes of violence, it still raises the question whether this pattern of thinking, too, does not involve dividing up recognition, in which case earlier questions regarding similar classifications would be reiterated. One could imagine distinguishing between instrumental violence (a form of violence aimed at a useful effect where harming the victim is only a means to an end and which is based on a non-aggressive need), emotional violence (a form of violence aimed at reducing internal states of tension that is based on an actual need for aggression) and expressive violence (the primary form of violence that serves the purpose of self-presentation). A criticism raised of these classifications is that often it is not possible to draw a clear distinction, since the different causal patterns (in the case of emotional-reactive aggression primarily aversive hostile and violent treatment by the environment, in the case of instrumental aggression the existence of successful models or the person’s own successes with aggressive behavior) may coincide in each individual case (cf. Nolting 1999: 149, 189)8

Hence there is much to support the third pattern of interpretation, according to which it seems to be possible to compensate for damage to recognition in individual integration dimensions by recognition gains in other dimensions. In that case, the crucial factor would be the balance of recognition. The choice of a specific pattern of action or a variation of it would then no longer be attributable to a specific injury to recognition in one or more integration dimensions. That would then mean that although the chosen pattern of coping was subjectively the one which the person expected to have the biggest effect in a given situation, the above-mentioned biographical dispositions (experiences, competencies, patterns of accountability) along with individual and social opportunity structures (integration into social milieus, etc) were likely to be of crucial significance in deciding which choice was ultimately made.

4. Conditions of Reaction to Denial of Recognition

Moderating variables seem to be emerging as similarly significant as they were in the discussion of individual theory perspectives, which raises the question whether the synthetic model put forward here can possibly be negated in the same way as numerous individual theories. Against this background, how should one imagine or conceptualize the correspondence between recognition or integration theory on the one hand and specific moderating variables on the other?

We intend to consider by way of example three groups of moderating variables (social competencies, patterns of accountability and social comparison processes) and to attempt to find a provisional answer to this question.

As regards social competences a simple logic seems identifiable from a deficit-theory perspective. This is that the better individuals are equipped with social competencies, the less susceptible they seem to be to dysfunctional patterns of coping. Consider, for example the pattern of indirect learning of violence (cf. 3. above) in which violence was classified as a symptom of lacking social competence (lack of empathy, identity disorder, lack of self-esteem). However, the finding here is not always as unambiguous as research would like it to be, since groups of persons with high self-esteem and an apparently stable sense of self-esteem have repeatedly been characterized as having an affinity with violence. Helsper in particular has tried to explain this contradiction by highlighting different ways in which relationships of mutual recognition fail in the socialization of children. Premature breaking of the child’s will or of the child’s autonomy leads via a badly damaged self-image to violence (which remains the only means of restitution for the self), as does giving in unconditionally to a child’s desires for omnipotence, since this leads the child to imagine that other people are only objects for it to control rather than subjects capable of recognition. Here, an extremely self-aware self corresponds with violence as an opportune strategy of action if others refuse to bow to this imagined greatness (cf. Helsper 1995: 137f). Baumeister and Bushman (2003: 484) also doubt whether there is a causal relationship between a low sense of self-esteem and aggression as a pattern of action, since they see a person’s unwillingness to allow feelings of shame as the key to aggression and this tends to apply more to people with high self-esteem that to those with low self-esteem. Accordingly, they say that violent patterns of action are most likely when people with a positive self-image come across people who attack their assessment of themselves, and that the most susceptible are people with a high but unstable sense of self-esteem. However, aggressive persons who react emotionally in particular are subjectively more keenly aware of threat than non-aggressive people are, which raises the question whether it is really possible to construe a subjective sense of threat and aggression independently of each other. If one agrees that the question of threat to the self plays a crucial part in the explanation, this would also mean that the subjective need for recognition had a crucial significance. Aggression as a mechanism for warding off feelings of inferiority would then only be conceivable as a relational connection.

As regards patterns of accountability, too, at first sight clear patterns of classification suggest themselves. Causes of the disruption or obstruction of objectives can be localized elsewhere. Individual attribution of responsibility whereby people attribute the cause of failure to themselves would tend to suggest depoliticizing patterns of coping (apathy, withdrawal). Social policy attributions of responsibility would tend to encourage, e.g. disenchantment with politics and rejection of the system, or even new, solidarity-based patterns of behavior. Collective patterns of accountability place the responsibility for a social problem with one or more social groups, which favors collective forms of reaction (prejudices, discrimination, bogeyman images). We referred above to the self-esteem-stabilizing function of prejudices and enemy concepts, which help people to uphold a positive self-image in the face of existing strains (cf. 3. above). That patterns of accountability are likely to be significant for the choice of specific patterns of coping with problems is shown inter alia by the example of the post-reunification transformation process in Germany. One can justifiably start from the assumption that the process of individualization in the new federal states of eastern Germany was and still is not so far advanced that people affected by far-reaching social and economic changes could hold themselves responsible. Especially where central problems such as the issue of mass unemployment are concerned, political and structural backgrounds are directly recognizable and the given situation can be experienced and interpreted as a collective fate. Since the individual pattern of interpretation (Beck 1986) could thus not yet have been very widespread, individual, self-directed reactions (e.g. self-destructive actions) would initially be less likely than collective political patterns of reaction (cf. Albrecht 1999: 37). This was confirmed empirically9. Although the principle of the effect of the patterns of accountability appears very clear, problems arise from the fact that the type of accountability can also fulfill a function for the receipt of recognition. In respect of the type of action we use as an example, violence, Schmidtchen has pointed out that in situations where the individual can no longer tolerate a specific degree of self-contempt, self-contempt turns to contempt for the social environment so that he or she is able to bear the pressure on his or her own personality. Therefore, especially in extreme situations when the recognition issue touches on existence one may no longer be able to assume accountability principles functioning in normal circumstances.

As for the role of social comparison processes, we must assume that social comparison processes not only relativize a person’s own state of integration (and hence the balance of recognition) but that in many cases they should not be constructed as independent of the question of integration at all. Every judgment of a state of integration (“am I integrated,” “am I treated with respect,” etc.) that is not self-directed in a comparison over time (“am I treated differently now than formerly”) is already the outcome of a social comparison process. Therefore social comparison processes must be included conceptually in the operationalization of integration or disintegration. In doing so one should note that here too the motive to preserve self-esteem plays a role, which is why in all aspects affecting self-esteem or personal well-being tendencies to compare “downward” are to be observed (cf. Herkner 1991: 455)10. This becomes immediately significant if we ask ourselves which indicators should be used to measure states of integration or disintegration. In the sub-dimension of communicative and interactive social integration, for example, the obvious thing would be to take verdicts on justice as a measure of integration. Along with justice of needs and services, justice of distribution would also be an important measure of the realization of integration. A look through the findings of empirical research on justice reveals that for years a stable majority of three quarters of the population has considered that the principle of just distribution in Germany has not been realized (cf. inter alia Bulmahn 2000). Nonetheless, at the same time, in population surveys such as ALLBUS similar majorities have answered in the affirmative the question whether they have a fair share compared with other people in this country (cf. inter alia Noll 1992; ZUMA 1996). This means that the majority of the people who consider that fair social distribution has not been realized feel fairly treated as individuals. This discrepancy is only explicable if one takes into account the effectiveness of social comparison processes in the form of downward comparisons. In other words, a group can still be found that, viewed subjectively, is worse off, so one’s own share is assessed as fair. Since the motive of preserving self-esteem is likely to influence the behavior of respondents the choice of parameters to measure integration is not without consequences. Thus it is likely to become necessary to include further planes of contemplation in the question of specific measuring of states of integration or disintegration, that is for each sub-dimension the individual, the collective and the social plane of judgment. Accordingly, states of integration and disintegration could only be analyzed as a whole by drawing a balance of the respective sub-viewpoints. At the same time, balances within a sub-dimension must on no account be drawn on the basis of a simplistic addition or “stepping-up logic.”

That social comparison processes, in addition to their significance as a measure when drawing a balance of integration and disintegration, are likely to be directly significant for the chosen example of action is indicated in further cases. In the case of violence at school, there appears to be a repetitive pattern in that in specific acts of violence on the one hand very successful students (best at sports, highest-achieving, etc.) are to be found on the side of the preferred victims and on the other the weakest, most discredited students (cf. for example the school massacre in Littleton, Colorado, the example of Tim the thug in Helsper 1995 etc.). This lends fuel to the idea that massive social comparison processes have taken place in the background. On the one hand the victims are those who seemed out of reach, in whom any comparison had to end in self-damage. On the other hand it is those who themselves became victims of social discrimination and exclusion with whom may have been compared and was treated accordingly.

Literature:

1 For the sake of clarity and for space reasons the arguments below are presented by way of example, taking the phenomenon of violence as an example. Analogical conclusions and parallel arguments for the other phenomenon areas mentioned are only of an indicative nature and as a rule take the form of comments.

2 The principle of learning a model by means of symbolic or representative reinforcement is in Schmidtchen’s estimation always subordinate to learning from experience, since in his opinion it always (which means only) functions when there are no other, stronger rewards that cover up the observed motives for action (cf. Schmidtchen 1997: 230). However, even learning from experience as the sole pattern of explanation runs up against limits in some cases (see section 3.).

3 It is therefore a matter of internalization processes beyond mere imitation and identification for which other motive structures can also claim validity (e.g. extrinsic rewards, identification with strength-promising idols to resist diffusion of identity, etc.)

4 From a gender-specific perspective, the image of hegemonic manhood now seems to be characterized by verbal assertiveness and cleverness coupled with economic and/or institutional power. Thus a man or youth who lacks access to this structure is thrown back to a special extent on to the traditional ideal of masculinity in which physical violence and the ability to demonstrate strength occupy a central rank (Möller 2001: 257f; cf. also Findeisen/Kersten 1999 and Scherr 1999).

5 An authoritative and participative style of upbringing that takes appropriate account both of the child’s needs and parental authority is essentially characterized by suggestions, guidance and recognition (cf. Hurrelmann 2002: 156f)

6 Eckert (1993: 370) especially has pointed to the fact that denigration (including ethnic denigration) of others is an adequate means of stabilizing self-esteem in situations of competitive pressure because failure is easier to bear if it seems to have been caused by the illegitimate means of others. Therefore “competition” and “compensation” are not reciprocally independent active mechanisms as Rippl (2003) suggests in her analysis of the genesis of xenophobic attitudes. The juxtaposition of “competition” as an active mechanism of deprivation theory and intergroup theory and “compensation” as a stabilizing mechanism of authoritarianism and anomie theory concepts is also tied down in formal ideological approaches. In the integration theory perspective pursued here (injury to recognition as a common nucleus) this formal separation does not seem to make much sense, besides which it cannot be confirmed empirically (cf. ibid.: 243, 247).

7 In Neumann’s view, the establishing of justice as a reply to the violation of norms is definitely connected with the motive of self-presentation when the aim is to convey, for example, the message: “I am strong and tough enough to rebel against injustice” (2001: 103)

8 Empirically, too, there are reservations as to the plausibility of the second pattern of thinking, since various surveys, for instance of politically motivated violence, have led to the same finding - that xenophobic violence is to a large degree perpetrated by youths accustomed to violence and that a targeted political function recedes behind a youth culture-influenced, masculine demonstration of strength (cf. Neidhardt 2002: 778; and previously Heitmeyer 1994: 47; König 1998: 186).

9 Cf. inter alia Silbereisen 1997: 576.

10 In addition, Wrosch and Heckhausen (1996: 126f) support the thesis of the functional ties of upward or downward comparisons. Accordingly, upward social comparisons would have the function of self-improvement by highlighting paths of action, while downward social comparisons fulfil the function of enhancing or protecting self-esteem.

Albrecht, G. (1999): Sozialer Wandel und Kriminalität. In: Albrecht H. J./Kury, H. (Hrsg.): Kriminalität, Strafrechtsreform und Strafvollzug in Zeiten des sozialen Umbruchs. Freiburg: Ed. luscrim, pp. 1-56.

Albrecht, G. (2001): Gewaltkriminalität zwischen Mythos und Realität. In: Albrecht, G./Backes, O./Kühnel, W. (Hrsg.): Gewaltkriminalität zwischen Mythos und Realität. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp, pp. 9-67.

Albrecht, G. (2003): Sociological Approaches to Individual Violence and Their Empirical Evaluation. In: Heitmeyer, W./Hagan, J. (eds.), International Handbook of Violence Research. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer, pp. 611-656.

Anhut, R./Heitmeyer, W. (2000): Desintegration, Konflikt und Ethnisierung. Eine Problemanalyse und theoretische Rahmenkonzeption. In: Heitmeyer, W./Anhut, R. (Hrsg.): Bedrohte Stadtgesellschaft. Gesellschaftliche Desintegrationsprozesse und ethnisch-kulturelle Konfliktkonstellationen. Weinheim: Juventa, pp. 17-75.

Baumeister, R./Bushman, B. (2003): Emotions and Aggressiveness. In: Heitmeyer, W./Hagan, J. (eds.): International Handbook of Violence Research. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer, pp. 479-493.

Beck, U. (1986): Risikogesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Bierhoff, H.U./Wagner, U. (1998): Aggression: Definition, Theorie und Themen. In: Bierhoff, H.U./Wagner, U. (eds.): Aggression und Gewalt: Phänomene, Ursachen und Interventionen, Stuttgart, Berlin, Cologne: Kohlhammer, pp. 2-25.

Bulmahn, Th. (2000). Freiheit, Sicherheit und Gerechtigkeit. Unterschiedliche Bewertungen in Ost- und Westdeutschland. In: ISI 23, pp. 5-9.

Cierpka, M. et al. (1997): Über Aggression und Gewalt bei Kindern in unterschiedlichen Kontexten. In: Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie, No. 3, pp. 152-168.

Eckert, R. (1993): Gesellschaft und Gewalt – ein Aufriss. In: Soziale Welt, No. 3, pp. 358-374.

Eisenberg, G. (2002): Die Innenseite der Globalisierung. Über die Ursachen von Wut und Hass. In: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte. Supplement to weekly newspaper Das Parlament. pp. 21-28.

Findeisen, H.V./Kersten, J. (1999): Der Kick und die Ehre. Vom Sinn jugendlicher Gewalt. Munich: Kunstmann.

Heitmeyer, W. (1992): Desintegration und Gewalt. In: Deutsche Jugend, Year 40., No. 3, pp. 109-122.

Heitmeyer, W. (1994): Das Desintegrationstheorem. Ein Erklärungsansatz zu fremdenfeindlich motivierter, rechtsextremistischer Gewalt und zur Lähmung gesellschaftlicher Institutionen. In: Heitmeyer, W. (ed.): Das Gewalt-Dilemma. Frankfurt am Main.: Suhrkamp, pp. 29-69.

Helsper, W. (1995): Zur „Normalität“ jugendlicher Gewalt: Sozialisationstheoretische Reflexion zum Verhältnis von Anerkennung und Gewalt. In: Helsper, W./Wenzel, H. (eds.): Pädagogik und Gewalt: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen pädagogischen Handelns. Opladen: Leske & Budrich, pp. 113-154.

Herkner, W. (ed.) (1991): Lehrbuch Sozialpsychologie, Bern: Huber.

Hodges, E.V.E./Card, N.A./ Isaacs, J. (2002): Learning of Aggression in the Home and the Peer Group. In: Heitmeyer, W./Hagan, J. (eds.): International Handbook of Violence Research. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer, pp. 495-509.

Hengsbach, Friedrich (1997): Der Gesellschaftsvertrag der Nachkriegszeit ist aufgekündigt. Sozio-ökonomische Verteilungskonflikte als Ursache ethnischer Konflikte. In: Heitmeyer, W. (ed.): Was hält die Gesellschaft zusammen? Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Auf dem Weg von der Konsens- zur Konfliktgesellschaft, Volumr 2. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, pp. 207-232.

Hurrelmann, K. (2002): Einführung in die Sozialisationstheorie. Weinheim/Basel: Beltz.

Hurrelmann, K. (1990): Familienstress, Schulstress, Freizeitstress. Gesundheitsförderung für Kinder und Jugendliche. Weinheim/Basel: Beltz.

König, H.D. (1998): Sozialpsychologie des Rechtsextremismus. Frankfurt am Main.: Suhrkamp.

Kaufmann, Franz-Xaver (1997): Schwindet die integrative Funktion des Sozialstaates? In: Berliner Journal für Soziologie, No. 1, pp. 5-19.

Möller, K. (2001): Coole Hauer und brave Engelein. Gewaltakzeptanz und Gewaltdistanzierung im Verlauf des frühen Jugendalters. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Neidhardt, F. (2002): Besprechungsessay: Rechtsextremismus – ein Forschungsfeld. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Year 54., No. 4, pp. 777-787.

Neumann, J. (2001): Aggressives Verhalten rechtsextremer Jugendlicher. Eine sozialpsychologische Untersuchung. Münster: Waxmann.

Noll, H.-H. (1992): Zur Legitimität sozialer Ungleichheit in Deutschland: Subjektive Wahrnehmungen und Bewertungen. In: Mohler, P.P./Bandilla, W. (eds.): Blickpunkt Gesellschaft, Vol. 2. Opladen: VS – Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 1-20.

Nolting, H.P. (1999): Lernfall Aggression: wie sie entsteht – wie sie zu vermindern ist; ein Überblick mit Praxisschwerpunkt Alltag und Erziehung. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Peters, H. (1995): Da werden wir empfindlich. Zur Soziologie der Gewalt. In: Lamnek, S. (ed.): Jugend und Gewalt. Devianz und Kriminalität in Ost West. Opladen: Leske & Budrich, pp. 25-38.

Petermann, F. (1998): Aggressives Verhalten. In: Oerter, R. (ed.): Entwicklungspsychologie: Ein Lehrbuch. Weinheim: Beltz, pp. 1017-1023.

Peuckert, R. (1997): Die Destabilisierung der Familie. In: Heitmeyer, W. (ed.): Was treibt die Gesellschaft auseinander? Frankfurt am Main.: Suhrkamp, pp. 287-327.

Ratzke, K./Cierpka, M. (1999): Der familiäre Kontext von Kindern, die aggressive Verhaltensweisen zeigen. In: Cierpka, M. (ed.): Kinder mit aggressiven Verhalten: ein Praxismanual für Schulen, Kindergärten und Beratungsstellen. Göttingen: Hogrefe, pp. 25-60.

Rippl, S. (2003): Kompensation oder Konflikt? Zur Erklärung negativer Einstellungen zur Zuwanderung. In: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Year 55., No. 2, pp. 231-252.

Scherr, A. (1999): Befunde der Rechtsextremismusforschung, Gründe und Ursachen der Attraktivität rechtsextremer Orientierungen für Jugendliche. In: Dünkel, F./Geng, B. (eds.): Rechtsextremismus und Fremdenfeindlichkeit. pp. 69-89.

Schmidtchen, G. (1997): Wie weit ist der Weg nach Deutschland? Sozialpsychologie der Jugend in der postsozialistischen Welt. Opladen: Leske & Budrich.

Schneider, U. et. al. (1990): Erstgutachten der Unterkommission Psychologie. In: Schwind, H.-D. (ed.): Ursachen, Prävention und Kontrolle von Gewalt. Vol. 2. Berlin: Dunker & Humblot.

Schubarth, W. (2000): Gewaltprävention in Schule und Jugendhilfe. Neuwied: Luchterhand.

Silbereisen, R. K. (1997): Viel erreicht, noch mehr zu bewältigen: Zum Bericht der KSPW über individuelle Entwicklung, Bildung und Berufsverläufe. In: Berliner Journal für Soziologie, No. 4, pp. 569-581.

Tedeschi, J. T. (2002): The Social Psychology of Aggression and Violence. In: Heitmeyer, W./Hagan, J. (eds.): International Handbook of Violence Research. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer, pp. 459-478.

Tedeschi, J.T./ Felson, R. B. (1994): Violence, Aggression and Coercive Actions. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Wrosch, C./ Heckhausen, J. (1996): Adaptivität sozialer Vergleiche: Entwicklungsregulation durch primäre und sekundäre Kontrolle. In: Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und pädagogische Psychologie, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 126-147

ZUMA (1996): Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften. ALLBUS, Mannheim.